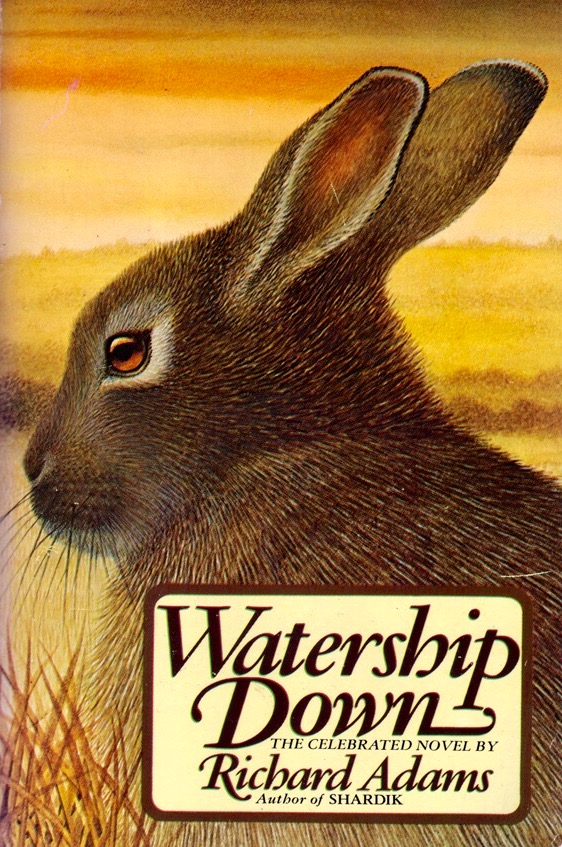

“If You’ll Come Along, I’ll Show You What I Mean”: Richard Adams and ‘Watership Down’

Richard Adams’ Watership Down is one of those books you pickup one day, only to find yourself suddenly on an adventure you’ll never forget. Neither parable nor allegory, the story of Hazel, Fiver, Bigwig, and their band of bucks fleeing the threat of human development is less like Orwell’s Animal Farm and more like Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. As has become part of the book’s legend, the tales that would become the novel originated as diversions for the author’s young daughters. So, it’s fair to say that Adams remained true to the stories’ child-like origins, and refrains from delving into political statements about the evils of modernization and the agricultural industrial complex. At the same time, the story doesn’t shy away from the pervasive fear that is constantly driving the book’s characters, as they deal with a thousand things that want to kill them!

As such, Adams’ narrative displays a deep appreciation for nature and a tactile writing style that relishes the look and feel of the places it evokes and the rabbit-eye view of the characters. Interestingly, Adams acknowledges only a single source for his copious knowledge of rabbits, namely The Private Life of the Rabbit by R M Lockley. Not only did Adams not possess a substantial amount of personal knowledge about rabbits—one might think that he spent a great deal of time observing these creatures in nature—but also, his research was remarkably limited. Then, again, Lockley’s treatise seems to have sufficed at informing Adams portrayal of rabbits confronting the upheaval of having their home, or warren, destroyed by farmers, which are a type of human that particularly loathes rabbits and regards them as vermin.

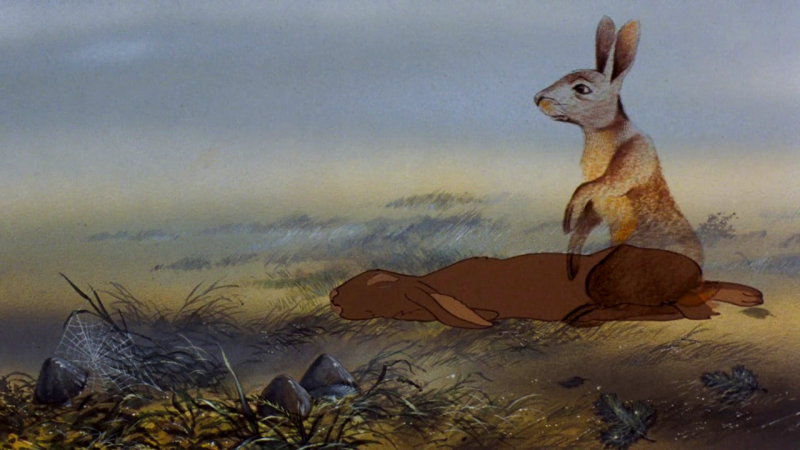

Watership Down, then, is epic story about the struggle for survival that many creatures endure in their never-ending quest to find shelter, food, and, above all, safety. As such, the story of the rabbits’ pursuit of a new home is archetypal and it’s at this level that the reader may empathize with the constant terror that these small beings face with the travails and hazards they must confront on their journey, most importantly General Woundwort and Efrafa. As Adams writes near the beginning of his story:

“It was getting on toward moonset when they left the fields and entered the wood. Straggling, catching up with one another, keeping more or less together, they had wandered over half a mile down the fields, always following the course of the brook. Although Hazel guessed that they must now have gone further from the warren than any rabbit he had ever talked to, he was not sure whether they were yet safely away: and it was while he was wondering—not for the first time—whether he could hear sounds of pursuit that he first noticed the dark masses of the trees and the brook disappearing among them.”

What Adams does incredibly well is create a mythic style of storytelling that is characteristic of the kind of preliterate narratives that have long been a part of human culture since the dawn of time. Adams even creates a rabbit based oral history about a cultural hero named El-ahrairah within the larger tale of Watership Down. Indeed, it’s precisely that ability to appeal to the reader’s mythic imagination that enabled Watership Down to truly become a timeless classic.